Authors: 1) Naman Raj Jain, and 2) Naman Jain

Bhutan, official the Kingdom of Bhutan, is a landlocked country of South Asia, situated on the Eastern ridges of the Himalayas bordered to India on South, East and West and to China on its North. Thimphu is the capital and the largest city with about 15% of the population. Throughout its history, Bhutan remained fragmented into small kingdoms and principalities until the establishment of the Wangchuk Dynasty in 1907 which continues to rule the country even today. Bhutan maintained a policy of isolationism until the mid-20th century, when it gradually started opening up to the outside world while still preserving its cultural heritage and traditions. In 2008, Bhutan transitioned to a constitutional monarchy with the enactment of a new constitution establishing a democratic system of government and holding its first democratic elections. The King of Bhutan is the head of state, while executive power is exercised by the Council of Ministers headed by the Prime Minister. The Parliament of Bhutan consists of two houses: the National Assembly (Lower House) and the National Council (Upper House). Members of the National Assembly are elected by the people, while members of the National Council are elected by local governments and nominated by the King. The Je Khenpo is the head of the state religion, Vajrayana Buddhism.

The Himalayan mountains in the north rise from the country’s lush subtropical plains in the south. In the Bhutanese Himalayas, there are peaks higher than 7,000 metres (23,000 ft) above sea level. Gangkhar Puensum is Bhutan’s highest peak and is the highest unclimbed mountain in the world. The wildlife of Bhutan is notable for its diversity, including the Himalayan takin and golden langur. Bhutan and neighbouring Tibet experienced the spread of Buddhism which originated in the Indian subcontinent during the lifetime of the Buddha. In the first millennium, tha Vajrayana School of Buddhism spread to Bhutan from the southern Pala Empire of Bengal. During the 16th century, Ngawang Namgyal unified the valleys of Bhutan into a single state. Namgyal defeated three Tibetan invasions subjugated rival religious schools, codified the Tsa Yig legal system and established a government of theocratic and civil administrators. Namgyal became the first Zhabdrung Rinpoche and his successors acted as the spiritual leaders of Bhutan, like the Dalai Lama in Tibet. During the 17th century, Bhutan controlled large parts of northeast India, Sikkim and Nepal.; it also wielded significant influence in Cooch Behar State.

Bhutan was never colonised, although it became a protectorate of the British Empire. Bhutan ceded the Bengal Duars to British India during the Duar War in the 19th century. The Wangchuck dynasty emerged as the monarchy and pursued closer ties with Britain in the subcontinent. In 1910, the Treaty of Punakha guaranteed British advice in foreign policy in exchange for internal autonomy in Bhutan. The arrangement continued under a new treaty with India in 1949, signed at Darjeeling, in which both countries recognised each other’s sovereignty. Bhutan joined the United Nations in 1971 and currently has relations with 56 countries. While dependent on the Indian military, Bhutan maintains its own military units. The 2008 Constitution established a parliamentary government with an elected National Assembly and a National Council.

Bhutan is a founding member of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), and a member of the Climate Vulnerable Forum, the Non-Aligned Movement, BIMSTEC, the IMF, the World Bank, UNESCO and the World Health Organization (WHO). Bhutan ranked first in SAARC in economic freedom, ease of doing business, peace and lack of corruption in 2016. In 2020, Bhutan ranked third in South Asia after Sri Lanka and the Maldives in the Human Development Index, and 21st on the Global Peace Index as the most peaceful country in South Asia as of 2024, as well as the only South Asian country in the list’s first quartile. Bhutan has one of the largest water reserves for hydropower in the world. Melting glaciers caused by climate change are a growing concern in Bhutan.

ECONOMY OF BHUTAN

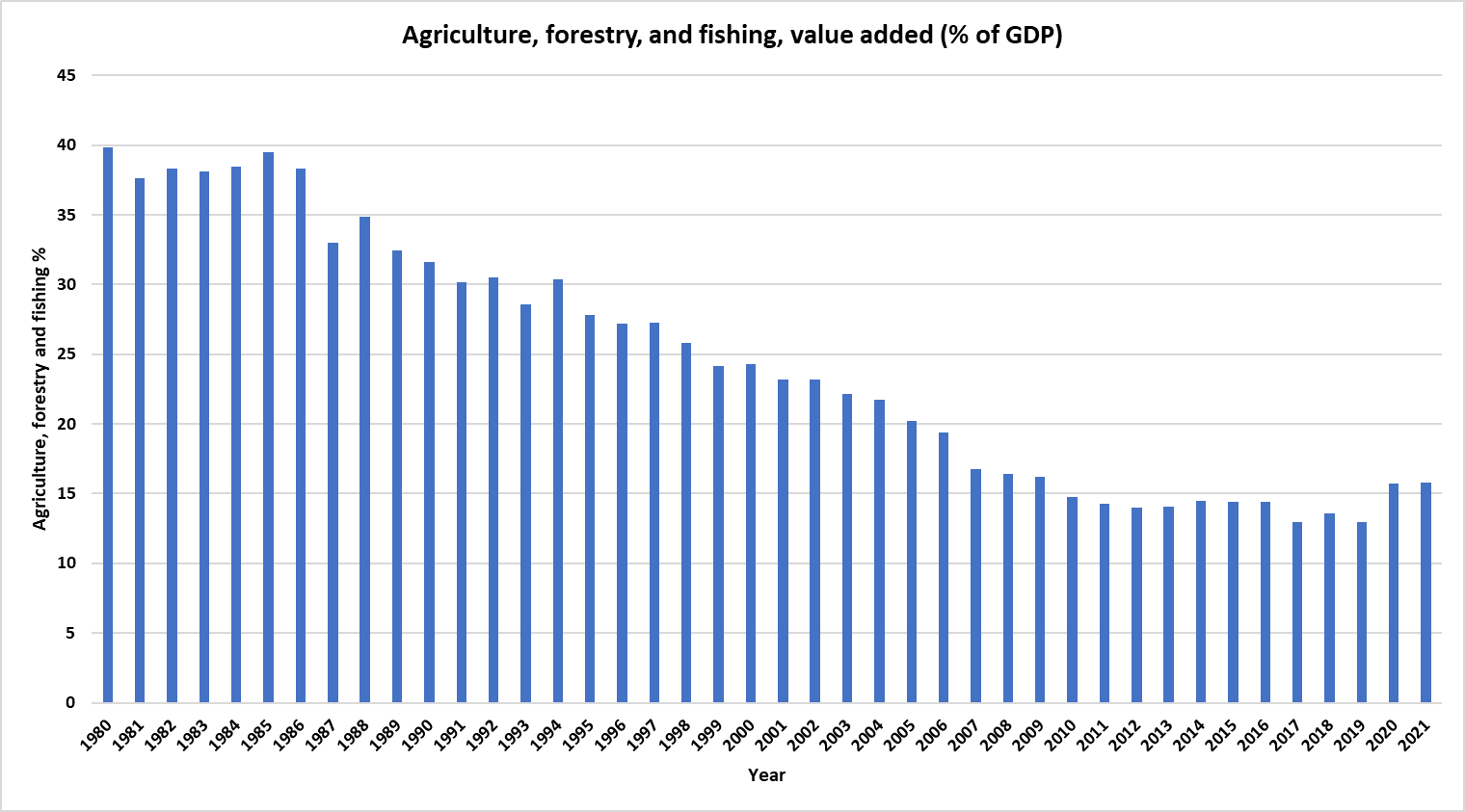

Bhutan has an agrarian economy. Agrarian practices mainly include subsistence farming and animal husbandry. Rice, chilies, buckwheat, barley, root crops, apples and maize are mainly produced in Bhutan. 56% of the Bhutanese population depends on agriculture, 22% on industry and the remaining 22% on services for their livelihood. 95% of the industries located in Bhutan are small and cottage scale industries. Around 79% of industries belong to the service sector, 10% to the production and manufacturing sector and the remaining to the contract sector.

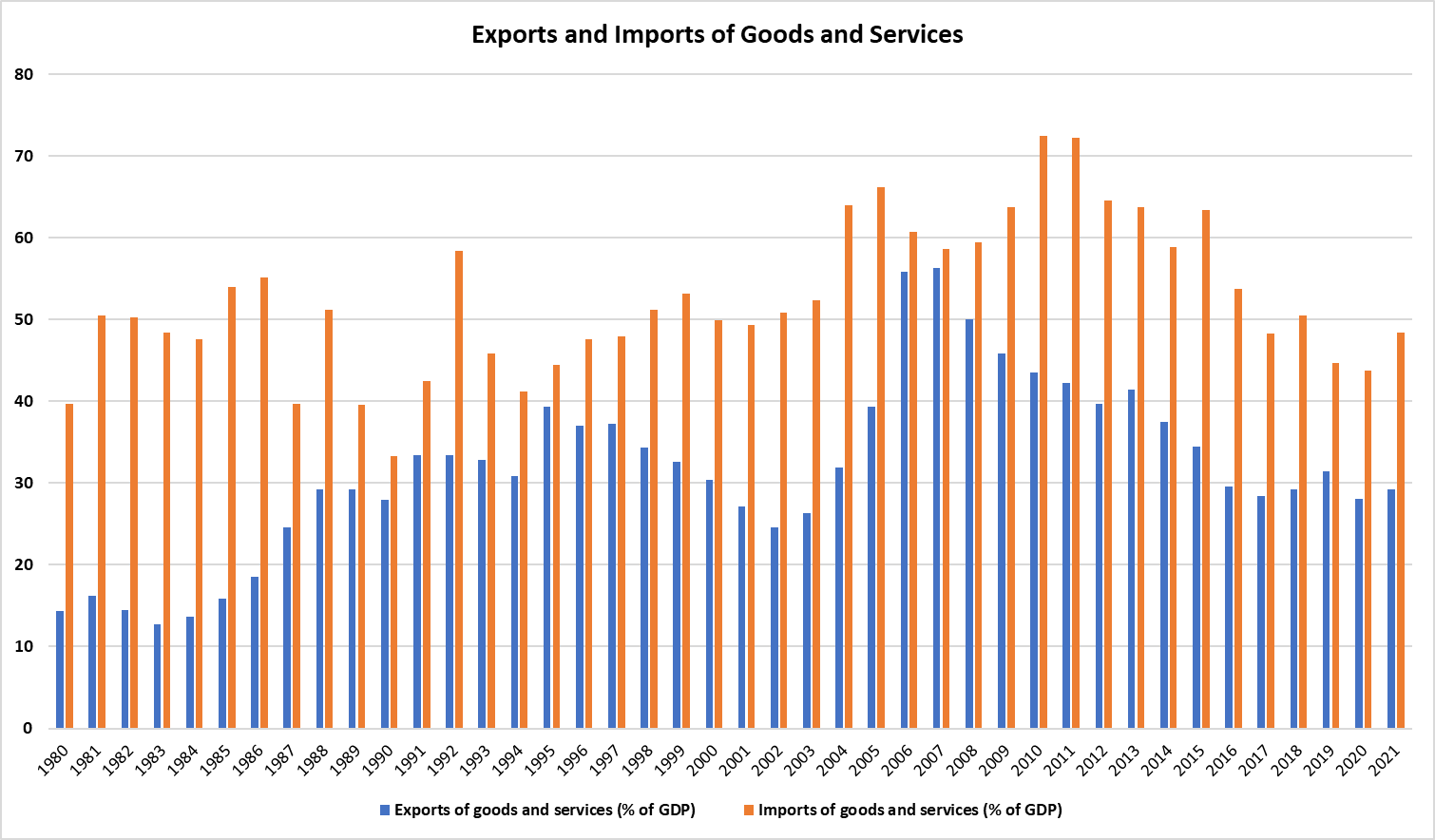

Industries bring innovation and investment, reduce poverty and rural-urban migration by creating employment opportunities and the also help in making Bhutan self-reliant. Bhutan is an importer of petroleum products, mineral products, base metals, machinery and electrical appliances, automobiles, wood, plastic, rubber, spices, and processed food. Around 80% of the imports are from India and the remaining from South Korea, Thailand, Singapore, Japan, China, and Nepal. 90% of Bhutan’s exports go to India and other export partners include Hong Kong, Bangladesh, Japan, Nepal, and Singapore. Electricity constitutes around 50% of the exports and other export items include metals, minerals, timber, raw silk, fruit products and rubber products.

Bhutan is dependent on India for financial assistance and migrant laborers for major infrastructural projects such as construction of roads and dams. Bhutan’s economy is very closely related to that of India with strong trade and monetary links.

All the economic programs which are brought by the government to uplift the economy keep in consideration country’s aim to protect its environment and cultural traditions. Since 1961 the economy of Bhutan has been governed by Bhutanese government’s five-year plans. Bhutan graduated from UN’s list of the Least Developed Countries on 8th December 2023.

Source: Macroeconomic Situation Report Second Quarter FY2023-24. Macro-Fiscal Policy Division. Department of Macro-Fiscal and Development Finance.

MACROECONOMIC OVERVIEW OF BHUTAN

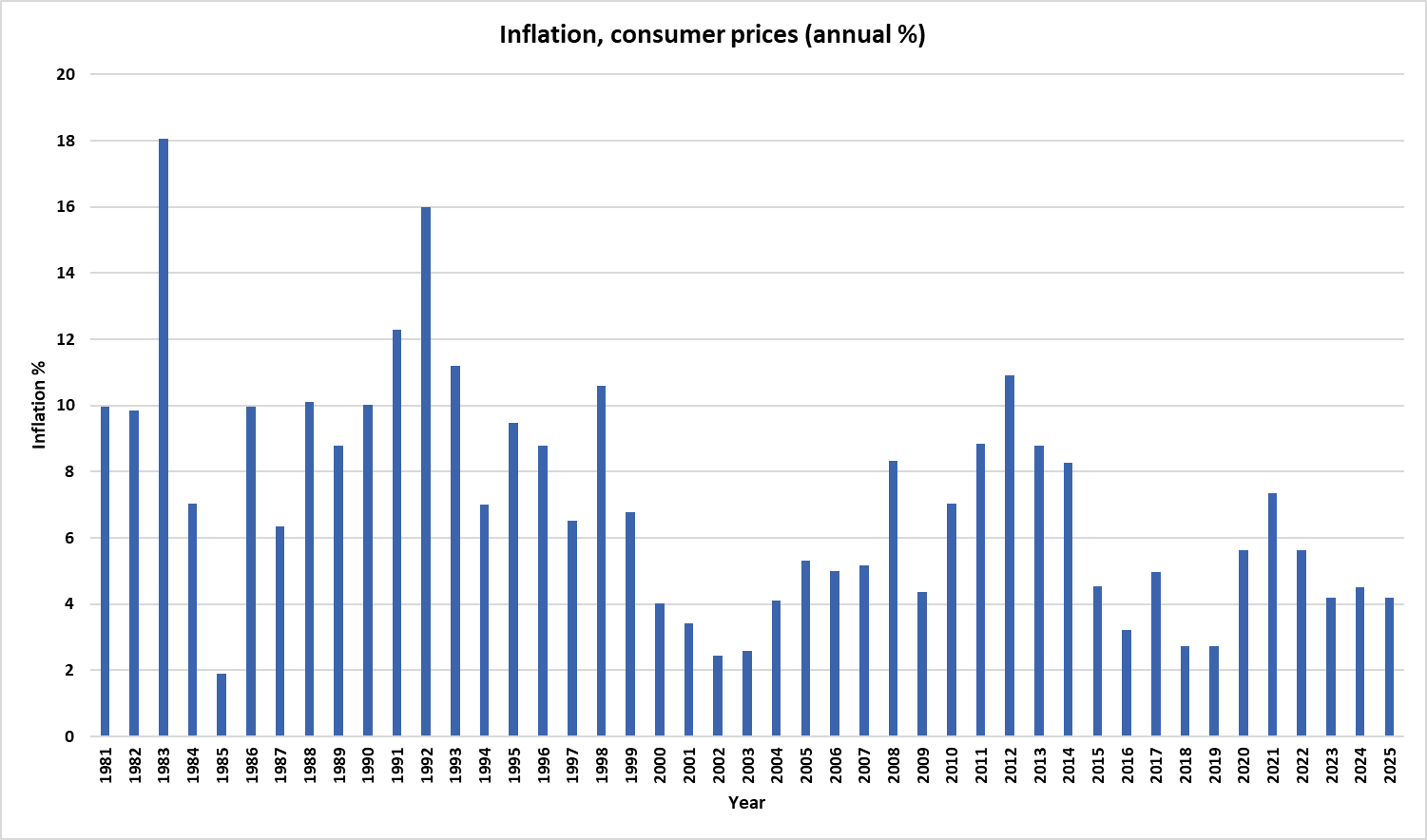

Bhutan has experienced rapid economic growth in recent decades, with real GDP growth averaging 7.5% since the 1980s. This growth has been driven by the public sector-led hydropower sector and strong performance in services, including tourism. Bhutan is classified as a lower-middle income country. Its GDP per capita was $3,491 in 2022, making it one of the richest countries in South Asia, though it still ranks 153rd globally. The total GDP of Bhutan was $2,653 million in 2022, ranking it 178th globally.

The real GDP growth rate is projected to decline to 3.2 percent in FY23/24. Overall growth is expected to be supported by higher growth in tourism-related services. On the demand side, growth is supported by private and public consumption, reflecting higher government spending. However, public investment is contributing negatively to growth due to a decline in capital spending. Medium-term growth is expected to be supported by a recovery in the non-hydro industry and services sectors, and by the commissioning of a new hydro plant.

Inflation is expected to remain elevated in the short-term owing to higher import prices, before moderating in the medium term. The incidence of poverty is estimated to decrease slightly to 0.4 percent and 7.9 percent in 2023, based on $3.65/day and $6.85/day, respectively. However, about 7 percent of the population will still be vulnerable to poverty.

The fiscal deficit is expected to increase to 5.83 percent of GDP in FY23/24 due to an increase in current spending following a major salary hike to address significant staff attritions. An increase in tax revenue will be offset by lower hydro profit transfers and external grants. Capital expenditures are projected to decline as the 12th FYP ended in June 2023, and capital spending is typically lower in the first two years of a new FYP. The fiscal deficit is expected to decline beyond FY24/25, reflecting a moderation in primary recurrent expenditure and increased hydro revenue.

The CAD is projected to decline to 21 percent of GDP in FY23/24 due to a large reduction in IT equipment imports, and to moderate further in the medium term, supported by an increase in tourism and electricity exports. International reserves are expected to increase to 6.2 months of import coverage in FY23/24.

Challenges facing the Bhutanese economy include high unemployment, especially among youth, as well as financial sector vulnerabilities due to high non-performing loans.

Bhutan is a small open economy, which is highly dependent on its exports and imports with the rest of the world, especially India. Since 1980s imports have dominated exports. Figure 3 shows that imports have risen since 1990s although they have been falling since 2011. Exports have been falling since 2007. The sale of hydropower is a very significant export item which contributed around 63 percent to Bhutan’s total exports. Indo-Bhutan hydropower cooperation began in 1961 with the signing of the Jaldhaka agreement. Cooperation in the hydropower sector between India and Bhutan is a true example of mutually beneficial cooperation, providing clean electricity to India, generating export revenue for Bhutan, and further strengthening the bilateral economic linkages. The two countries have successfully concluded several power project agreements.

Dependence on the hydropower sector poses risks to Bhutan as the sector’s growth plays a vital role in the country’s growth. In addition, the volatility observed in the hydropower growth is translated to volatility in the overall growth levels. Hence, it is vital for the government of Bhutan to seek to improve and diversify production in other sectors, such as tourism, agriculture, etc.

FISCAL DEFICIT AND DEBT

In the 2022/23 annual budget report, the finance minister reported a fiscal deficit of BTN 22.882 billion, which is 11.25% of the GDP. This followed a deficit of more than BTN 17 billion in the 2021/22 budget year. This level of deficit far exceeded Bhutan’s 12th plan target of keeping the deficit under 3% of the GDP. In FY 2019/20, Bhutan ran budget deficits of -2% and -6.2% of its GDP, respectively. As of June 2022, Bhutan’s total external debt was BTN 229.52 billion, an increase of 3.3% or equivalent to BTN 7.4 billion from March this year. Similarly, domestic debt was BTN 28.06 billion, an increase of 9.7% or BTN 2.49 billion from March this year. The increase in domestic debt was due to the new issuance of government bonds for deficit financing. Bhutan’s total national debt as of June 2021 stood at BTN 238.398 billion, according to the annual audit report 2020/21 released in November 2021. This is 129.06% of the GDP. Bhutan’s GDP during the year was recorded at BTN 184.715 billion.

BHUTANESE CONCEPT OF GROSS NATIONAL HAPINESS

In 1629, Bhutan’s legal code stated, “if the government is not able to ensure the happiness of its people, then there is no need for a government.” However more recently in 1970s the fourth King of Bhutan, His Majesty Jigme Singye Wangchuck, formally made the happiness of his people a concrete and explicit policy objective to be measured. A measurement tool was developed to help government and non-government organisations and businesses in Bhutan determine the GNH. The measurement uses nine domains with 33 indicators. The nine domains are psychological wellbeing; health; education; time use; cultural diversity and resilience; good governance; community vitality; ecological diversity and resilience; and living standards.

This philosophy, which has been enshrined in the country’s constitution, emphasizes the importance of balancing economic progress with the preservation of the nation’s rich cultural heritage, its pristine environment, and the overall well-being of its citizens Bhutan’s pioneering approach has not only gained the attention of global leaders and organizations but has also inspired a shift in how we perceive progress. As the UNDP and OECD support the need for multidimensional indicators and policy reforms, Bhutan’s insights and experiences will play a crucial role in shaping the global conversation on wellbeing. The GNH Index’s influence has the potential to change the way nations prioritize their citizens’ holistic wellbeing and safeguard the rights of future generations. Bhutan’s journey towards Gross National Happiness serves as a guiding light for a future where the pursuit of prosperity aligns with the pursuit of happiness. Bhutan’s pioneering approach has not only captured the attention of global leaders and organizations but has also inspired a shift in how we perceive progress. According to the 2022 GNH Index, 48.1% of those aged 15 years and above were classified as happy. The percentage of happy people increased over time, from 40.9% in 2010 to 48.1% in 2022.

The measurement of Gross National Happiness will also help a lot in policy making as the effect various policies can be analyzed on people’s happiness also with the help of GNH apart from other economic indicators.

LEGAL AND POLITICAL SYSTEM IN BHUTAN

Bhutan’s national parliament has two chambers the National Council, and the National Assembly. Bhutan’s constitution grants its citizens universal adult franchise and secret ballots. For the National Council, which is nonpartisan and seen as a house of review, one member is elected for each district (dzongkhag), regardless of its population size.

The constitution guarantees freedom of assembly and association, but in practice, there are restrictions on these principles. Citizens can join political parties approved by the Election Commission. Protests or demonstrations are permitted but must be approved by the government beforehand. Public protests, however, are viewed as non-Bhutanese behaviour. Freedom of association is limited to groups that are “not harmful to the peace and unity of the country.” As a result, civil society organizations (CSOs) working on refugee or human rights issues, as well as other sensitive policy areas, are not allowed to operate. All CSOs must register with the government. Due to the predominantly rural subsistence nature of life in Bhutan, the scarcity of large organizations, and the lack of government support for unions, there are no trade unions.

Bhutan’s constitution guarantees freedom of expression, but the exercise of this principle remains constrained in practice. According to the 2022 World Press Freedom Index, Bhutan has ranked 33rd out of 180 countries, a significant improvement from its 65th place in 2021 and 94th place in 2018. Editors of both print and online media, however, have complained that the government restricts media access to official information by imposing gag orders on government officials.

Bhutan’s constitution strongly emphasizes the rule of law. The judiciary is the guardian of the constitution and the final authority regarding its interpretation. The Supreme Court stands at the top of the court hierarchy. The decisions of the lower courts can be appealed upwards, and each level of the court system maintains its independence.

Out of Bhutan’s total population, 75% adhere to Mahayana Buddhism. The constitution declares that religion does not interfere with politics and that religious institutions and personalities must remain unpolitical. Thus, the state is officially secular, and no political activity by the Buddhist establishment can be observed. The personnel of religious institutions are prohibited from voting or standing in elections. In spite of all these provisions, however, the constitution does state that preserving the country’s religious heritage of Buddhism is important and that society is “rooted in Buddhism.” Buddhism is closely tied with the elites, and there is a strong bias against Hindus in particular. Since the 1980s, Bhutan’s “One Nation, One People” policy has sought to promote a uniform religious and cultural identity. The national flag and emblem also draw from Buddhist symbolism.

PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION

Bhutan has a generally well-functioning system of public administration, involving central ministries in the capital and their decentralized offices in the districts (dzongkhags). In recent years, there have been calls to modernize the civil service throughout the country. Corruption and poor performance remain major challenges for administrative services. In 2022, the government subjected senior officials to performance tests in an attempt to remove poor-performing bureaucrats. Civil service employees suffer from low morale, poor management, and a high attrition rate. In November 2022, Bhutan enacted a Civil Service Reform Act that reorganized various government departments and agencies to achieve greater efficiency.

FOREIGN POLICY OF BHUTAN

“The fundamental goal of Bhutan’s foreign policy is to safeguard the sovereignty, territorial integrity, security, unity, and enhance the wellbeing and economic prosperity of Bhutan. The realization of this goal hinges on the maintenance of friendly and cooperative relations and collaboration with all countries to promote a just, peaceful, and secure international environment.”

Bhutan has remained isolated from the rest of the world for a greater part of time. Television did not come to Bhutan until 1999. For years, the country cut itself off, fearing that outside influences would undermine its monarchy and culture. Radio broadcasting began in 1973, and the internet arrived in 1999.

With the formation of a theocratic independent government in Bhutan by Ngawang Namgyel Bhutan established diplomatic and monastic ties with Nepal, Sikkim and Ladakh. After the Dual War between British India and Bhutan, Bhutan again started following a policy of self-isolation. Bhutan maintained friendly relations with the British and ensured that they do not enter in Bhutan.

When the British departed from India in 1947 India- Bhutan friendship treaty was signed between India and Bhutan in 1949 which formalised Bhutan’s relations with newly independent India. State visit of the Third King of Bhutan to India as the Chief Guest in India’s Republic Day Celebrations in 1954 and the historic visit of the Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru to Bhutan in 1958 laid the foundation of very strong Indo-Bhutan international relations.

With the help of India in 1971 Bhutan became a part of UN and started developing its foreign relations, a departure from its self-isolationist policy. Bhutan started receiving assistance when it became a member of the IMF and the World Bank in 1981. Bhutan had made diplomatic relations with 22 countries until 2003. Currently Bhutan has diplomatic relations with 54 countries and the European Union. Bhutan has friendly and cooperative relations with its immediate neighbour in the north the People’s Republic of China.

Article 20 of the Bhutan’s constitution states that the foreign relations of Bhutan come under the Druk Gyalpo who acts on the advice of the Prime Minister of Bhutan and Lhengye Zhungstog.

This is blog article has been written by Mr. Naman Raj Jain (NRJ), jointly with Mr. Naman Jain (NJ).

Mr. Naman Raj Jain is an undergraduate student at Shyam Lal College, University of Delhi, Delhi, India.